100 Years! First Part of “The Good Soldier Švejk” Was Published on March 1, 1921

March 1st marks the 100th anniversary of the original publication of the first part of Jaroslav Hašek’s satirical masterpiece The Good Soldier Švejk and His Fortunes in the World War.

The four-part book made its author famous and found a permanent place in world literature. Since its original publication, the adventures of Hašek’s good-humored main character have been translated into 54 languages, including Chinese and Arabic.

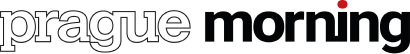

The central character in the novel, Josef Švejk, a dealer in stolen dogs in civilian life, is a Czech soldier who makes himself appear a fool to get around his superiors and fights a peculiar and often hilarious war of attrition against the difficult circumstances he finds himself in.

Švejk is a survivor, an amiably simple-minded, middle-aged man who never takes offence or gets angry, who walks through life with a sweet smile on his face, a survivor with a ready fund of cheerful stories about friends and acquaintances, which are appropriate for every situation he finds himself in, no matter how challenging, happy as long as he has a pint in one hand and his pipe in the other.

As Cecil Parrott notes in the introduction to a 1974 edition: “Švejk speaks most of the time in double-talk. He pretends to be in agreement with anyone he is dealing with, particularly if he happens to be a superior officer. But the irony underlying his remarks is always perceptible.” Švejk appears desperate to get to the front, for example, “by protesting his patriotism and devotion to the monarchy, when it is clear that his actions only impede the achievement of his proclaimed objective.”

Inspired by real life

The Good Soldier Švejk is a novel that is far more inspired by Jaroslav Hašek’s own life and varied experiences than any Cervantes or Rabelais.

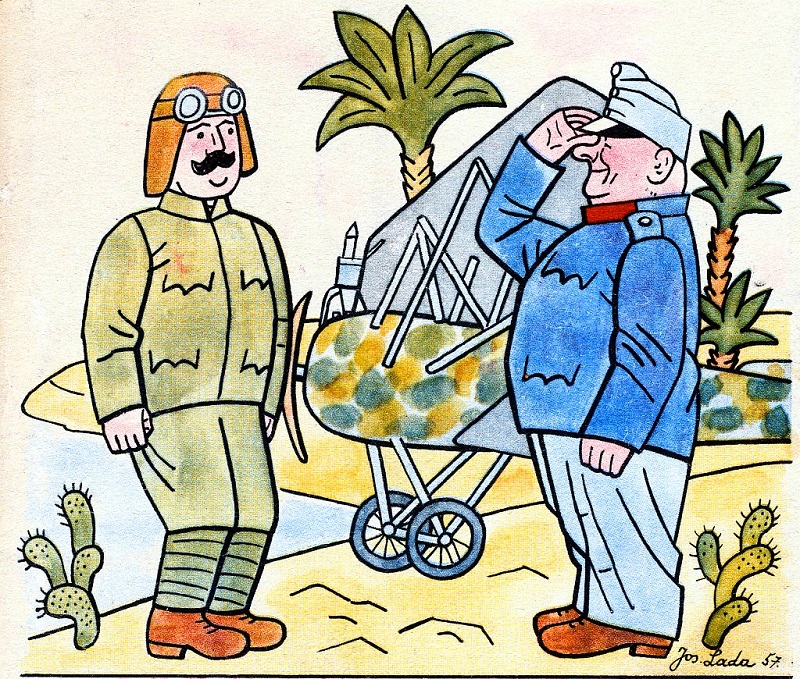

Švejk’s route to the front is described in detail and largely corresponds to the author’s own journey to the front in Galicia in the early days of July 1915. Several of the characters and situations are borrowed directly from author’s own surroundings and experiences. Despite the characters in the novel often being caricatures that never fully correspond to their real-life counterparts, they are still recognizable, even down to biographical details.

Although the novel is fiction it may therefore to a degree be read as a historical document. The author’s diverse background and extremely wide knowledge is obvious throughout: there are detailed descriptions of drinking binges, of the Catechism, preparation of meals, historical events, stay in lunatic asylums, religious rituals, dog breeding – all of it based on the author’s own experiences.

What was never written

If the author hadn’t died before he could finish volume four of the planned six, we can assume that Švejk, like his creator, would have let himself get captured by the Russians, served in the Czechoslovak Legions, worked for the Bolsheviks and eventually ended up in Siberia.

Hašek’s detailed plan for his good soldier we will never know, but it can be taken for granted that he planned to cover the time in Russia, including the Civil War. To what extent the satire would have been directed against the Legions and the Bolsheviks we can only guess, but to judge from what Hašek actually wrote in Russia (and after his return) they would not have been spared.

That said, the calibre would probably not be as heavy as that directed against Austria-Hungary in the first four parts of the novel. The Bugulma-stories that appeared in early 1921 indicate a more conciliatory tone.

The return that never was

For sure Jaroslav Hašek would have let Švejk return unhurt, let him drink his Velké Popovice beer at U kalicha, this time with Sappeur Vodička, without the instruments of power and detective Bretschneider poisoning the air with their lingering odour.

What he was to experience from mid-July 1915 until his return to Prague in 1920 we may well speculate on, but the author would surely have continued to roughly align the itinerary of his literary hero to his own.

Support Prague Morning!

We are proud to provide our readers from around the world with independent, and unbiased news for free.

Our dedicated team supports the local community, foreign residents and visitors of all nationalities through our website, social media and newsletter.

We appreciate that not everyone can afford to pay for our services but if you are able to, we ask you to support Prague Morning by making a contribution – no matter how small 🙂 .